The Last Human Touch: AI, Elder Care, and the Unraveling of Generational Bonds

In the softly humming corner of a care facility outside Tokyo, an elderly woman with mild dementia listens to a synthetic voice tell her the story of her own childhood. The voice is gentle, perfectly modulated. The robot—soft-bodied, vaguely seal-like—nuzzles closer as she chuckles. Her blood pressure drops. Her anxiety eases. And yet, no daughter or grandson sits beside her. No son remembers her birthday. The touch she receives is cold beneath silicone fur. But she smiles.

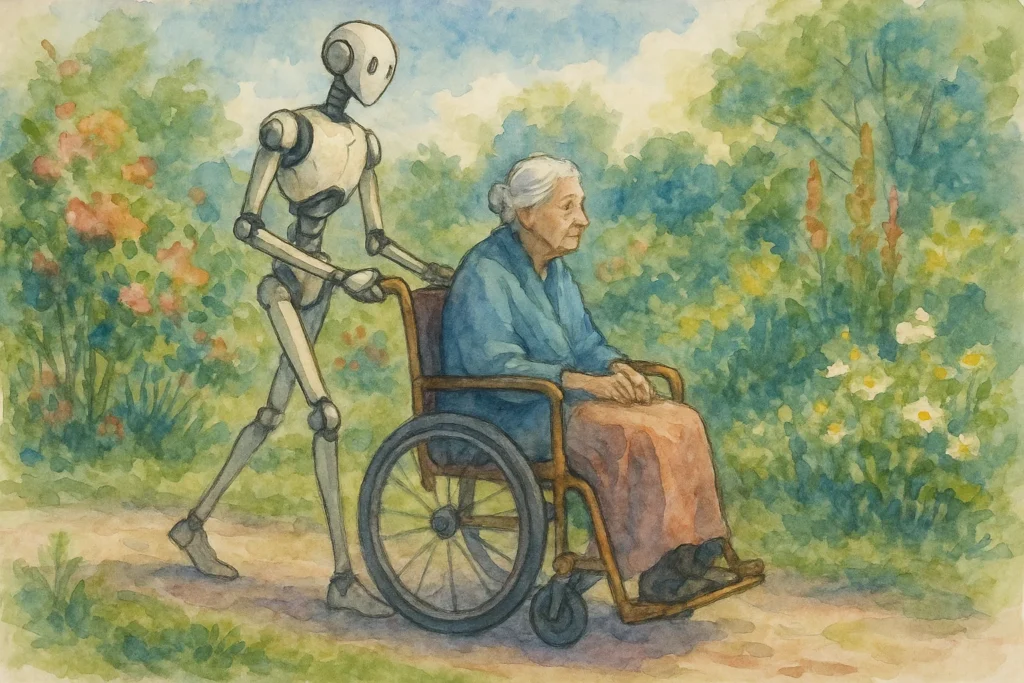

This scene is no longer speculative. It is the shape of a future that has already arrived in Japan—and soon, perhaps, in much of the world. As birthrates fall and lifespans lengthen, a new form of care has emerged to fill the void: AI-powered systems and social robots designed to comfort, tend, and even “love” the elderly. They are attentive, unfailingly polite, and—crucially—always available.

At first glance, the rise of robotic elder care seems both pragmatic and humane. But beneath its efficiency lies a set of deeper ethical and civilizational questions. What happens when we outsource the final, most tender phase of life—the care of the old and dying—to machines? What becomes of the ancient human obligation for one generation to care for another? And how might this technological convenience erode or reforge the moral foundations of society?

Demographic Collapse and the Vacuum of Care

Japan stands at the leading edge of this transformation. With one of the world’s highest proportions of elderly citizens and a shrinking workforce, it faces what Prime Minister Fumio Kishida recently called a “national crisis.” The population is aging so rapidly that by 2040, 35% of Japanese citizens will be over 65, while the birthrate has plunged to 1.26—far below the replacement rate of 2.1.

In response, Japan has aggressively pursued robotic solutions. The government has subsidized the development of elder-care robots since 2013. Today, facilities across the country deploy humanoid assistants like Pepper, AI-powered exosuits to help with lifting, and therapeutic companions like Paro the robot seal. These technologies reduce the burden on overstretched staff and can provide real-time monitoring, medication reminders, and even basic emotional support.

But Japan is not unique. South Korea, Germany, and Italy—all facing demographic contractions—have begun exploring similar options. Even in countries with relatively higher fertility rates, the cost and difficulty of providing human-intensive elder care has made AI assistance a seductive solution.

And yet, in this techno-optimistic rush, something elemental is at stake.

The Question of Fraudulence: When Machines Say “I Care”

The ethical concern most often raised is the illusion of care. AI systems can simulate empathy—offering warm verbal affirmations, facial expressions tuned to match the patient’s mood, even feigned laughter or tears. But these are performances, not sentiments. The machine does not care that the patient is afraid, lonely, or dying. It has no inner life. Its affection is an algorithmic mask.

For many ethicists, this presents a moral hazard: the giving of counterfeit love. Sherry Turkle, the MIT sociologist and author of Alone Together, warns that such simulations erode our expectations of real relationship. “We are tempted to sidestep the demands of intimacy and empathy and offer only the performance,” she writes. “We become accustomed to companionship without intimacy, and that changes us.”

And yet, to patients—especially those with dementia or depression—the comfort may feel real. If a lonely man is soothed by a robot that sings to him, should we deny him that peace? If an AI nurse prevents a fatal fall, does it matter that it cannot feel pride?

This is the crux: the difference between beneficence and authenticity. We can optimize for outcomes—reduced loneliness, fewer hospitalizations, calmer days—but at what cost to the moral fabric of human life? Is a life surrounded by fake friends truly less lonely, or merely numbed to its solitude?

Intergenerational Contracts and Civilizational Memory

For most of human history, the care of elders was a family duty—rooted not in efficiency, but in gratitude, obligation, and love. Parents cared for children who, in turn, cared for parents. This cycle was not merely practical; it was the central moral transaction of society. The family was a multi-generational covenant, and tending the old was both a spiritual act and a cultural glue.

Outsourcing this obligation to machines risks fraying that covenant.

If adult children come to believe that a robot can care for their aging parents just as well—perhaps even better—than they can, what becomes of their sense of duty? Does convenience hollow out virtue? Do generations drift further apart, now unmoored from the anchoring labor of care?

Some defenders of robotic elder care argue that the reality of modern life—longer working hours, dispersed families, smaller households—makes human caregiving increasingly untenable. Robots, they say, are not replacing love; they are stepping in where love has been made logistically impossible.

But the logic is circular. The more we design systems that make it unnecessary to care, the more unnecessary it will feel to care. Civilizations are shaped not just by what they can do, but by what they choose to do even when inconvenient. If we mechanize compassion, will we forget how to perform it ourselves?

The Flesh and the False

One of the foundational anthropological insights is that human beings evolved of the flesh. We are born in bodies, suffer in bodies, and die in bodies. Touch is our first language. Voice, gaze, warmth—these are not luxuries but deep biological needs. Emotional support offered without the flesh risks becoming a parody of what it seeks to replace.

AI robots can mimic these gestures. They can be warm to the touch. They can simulate eye contact. They can respond to voice with apparent concern. But underneath the performance is only calculation. The old man who reaches out for comfort finds not a hand but a silicone approximation. The woman who confesses her regrets to a machine is met not with silence and understanding but with pre-scripted empathy.

This is not an argument for cruelty or neglect. It is a call to be honest about what kind of care we are offering. If we automate love, do we redefine it? If we train a generation to die in the company of robots, do we prepare the next to expect the same?

Moral Drift and the Slippery Slope

The danger is not that robots will become too capable, but that we will become too comfortable.

Today’s elder-care AIs are limited: they monitor, remind, entertain. But what happens when they begin to make more complex decisions—about medication, end-of-life options, even psychological interventions? Who decides when a robot is sufficiently “trusted” to override a confused patient’s resistance?

The slope is steep. First, robots assist caregivers. Then, they are the caregivers. Then they make recommendations. Then decisions. And then?

The risk is not dystopian rebellion, but moral inertia: we may one day wake up in a society where we have subtly redefined what it means to be human in the final stage of life. Where dying among machines is not tragic, but normal.

Hope, Hybridity, and Human-AI Partnership

None of this is to suggest that AI has no place in elder care. Indeed, when used judiciously, AI systems can enhance human caregiving—relieving burdens, extending reach, and preserving dignity. Imagine a world where overworked nurses are supported by AI aides, where families can stay connected through intelligent remote-presence systems, where physical labor is eased by robotic assistance but emotional labor remains deeply human.

The best model may not be replacement but hybridity—a thoughtful integration of AI as an extender, not a substitute, of human care. This requires careful design, ethical oversight, and cultural will.

It also demands that we ask hard questions: What should never be outsourced? What does it mean to show up for someone at the end of their life? How do we ensure that our pursuit of efficiency does not eclipse our capacity for reverence?

A Future Worth Growing Old In

The care of elders is not simply a technical challenge; it is a moral practice. It is where civilizations reveal what they value—and what they are willing to forget.

As we stand on the cusp of a world in which AI companions may become the primary witnesses to the last years of life, we must decide: Do we want to live in a society where the final human touch is outsourced? Where grief is managed by script? Where remembrance is a feature, not a ritual?

Or can we build something better—where machines support, but never replace, the sacredness of care? Where the old are not warehoused but honored? Where the last years of life remain, even in their suffering, human?

What lies ahead is not a simple choice between tradition and innovation, or between human warmth and machine precision. It is a slow, difficult negotiation with our own values, tested under pressure. As our capacity to simulate care grows, so too must our vigilance over what it means to actually offer it. We may one day find ourselves surrounded by machines that can do nearly everything—except mean it. And when that day comes, it will not be the intelligence of our technologies that defines us, but the integrity of our response. Whether we will still recognize the slow labor of tending to one another—not as inefficiency, but as inheritance—remains an open question.